The Centennial Museum's Chihuahuan Desert pages have a nearly complete list of mammals of the desert region, many with pictures and basic information. From our point of view, being mammals ourselves, the class Mammalia is of considerable importance to the desert, though the backboneless might object.

The only marsupial in the Chihuahuan Desert is the Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana). The opossums entered North America from South America after the Central American land bridge formed during the Pliocene. Isolated populations in the northern part of the Chihuahuan Desert appear to be introductions from farther east, where they are native. In tune with the long separation between marsupials and placental mammals (probably happening sometime during the Cretaceous), there are a number of differences. These include, in this order of marsupials, more teeth than occur in placentals. Most notably, there are five upper and four lower incisors on each side of the jaw as compared to three in both the upper and lower jaw of the primitive placental mammal. The cheekteeth also are different, with the opossum having three premolars and four molars whereas the primitive placental had four premolars and three molars. Other differences include a pair of bones (epipubic bones) not found in placentals and a reproductive system resulting in birth of what are basically embryos.

The order Soricomorpha (earlier literature will have it as order Insectivora) includes the shrews. Most shrews occur in northern and north-temperate zones that are well watered. In the Southwest, most species occur in the better watered mountains. The Desert Shrew (Notiosorex crawfordi), however, is arid adapted and occurs in the Chihuahuan Desert (the type locality is El Paso, Texas).

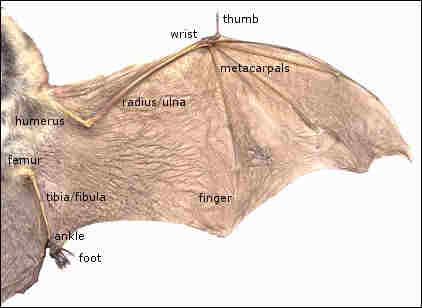

Bats are members of the order Chiroptera (literally, hand wing). Bat are the only flying mammals, one of only four groups of animals that have achieved flight (insects, the extinct pterosaurs, and birds are the others). Talking about "the bat" is as ridiculous as talking about "the mouse". The order Rodentia is the largest of the mammalian orders; the Chiroptera is the second largest. Because of their largely nocturnal habits, few people realize the great variety, and myths abound. Contrary to folklore, bats have no interest at all in becoming entangled in women's hair nor are they disciples of the devil.

The right side of a bat showing the flight structures with the main skeletal supports labeled.

Bat are excellent flyers, but owe control of the night skies largely to their highly developed sense of echolocation. High frequency sounds are emitted from mouth or nose, and the echos received when the sound waves bounced back from objects allow the bats to determine such things as prey size, texture (e.g., moth versus beetle bodies), distance, speed of movement, and direction of movement. Thanks to this high-grade sonar, bats are able to function nicely in pitch blackness. The various facial decorations that give so many bats character for the most part appear to be adaptations involved in echolocation.

Although we tend to think of bats as feeding on insects (and indeed, many do), their ecological niches are far broader than that. Various species feed on nectar (that is, they are

nectivorous) and pollen, on fish (piscivorous), on small vertebrates (carnivorous), on fruit (frugivorous), and on blood (sanguivorous). Most of the bats people encounter in the United States are

insectivorous, but in the southern Southwest and south into Mexico, other types appear. Although the temperate regions have a respectable chiropteran fauna, the tropics are the strongholds of the order in both the New and the Old World.

chiropteran fauna, the tropics are the strongholds of the order in both the New and the Old World.

The Mormoopidae is represented in our region by a single species, the Ghost-faced Bat (Mormoops megalophylla), and the Phyllostomidae by three species. The latter are nectivorous and important as pollenators of agaves in our region. Such bats are characterized by relatively weak dentition, long snouts, and long tongues.

Skull of a nectivorous bat, Leptonycteris yerbabuenae. Laboratory for Environmental Biology specimen. Photograph by A.H. Harris.

The family Vespertilionidae is the largest family in the North American temperate zone. At least 17 species are found in the Chihuahuan Desert. All are insectivorous, though a variety of strategies are utilized to gather prey. Many hunt flying insects, while the gleaners tend to pick prey items from surfaces such as leaves. Several species usually are found feeding over large bodies of water. The Pallid Bat will attack scorpions and centipedes on the ground.

Whereas most of our bats have the tail enclosed almost entirely in a membrane (the interfemoral membrane) that spreads between the hind limbs, members of the Molossidae can have the tail extend well beyond the membrane—thus the common name, free-tailed bats. The Mexican Free-tailed Bat (Tadarida brasiliensis) forms huge maternity colonies, up to a number of millions of individuals. The colony at Carlsbad Cavern National Park is the best known, but there are others. Some former colonies have been almost wiped out by pesticides, and the Carlsbad bats are greatly diminished in number. As with many predators, contaminents in the bodies of their prey become concentrated in the predator with drastic results.

The order Primates is limited to our own species, Homo sapiens. Humans were present by at least 11,500 radiocarbon years BP (Before Present, which actually means 1950), and probably considerably earlier. Radiocarbon years are somewhat different from calendar years in that the formation of the radioactive 14C that is used varies somewhat through time. As a result, radiocarbon years vary somewhat from calendar years; in the time frame we're involved in, the radiocarbon dates are somewhat too young. For example, a radiocarbon date of 11,500 is a calendar date of approximately 13,400 BP.

The order Carnivora includes the families Canidae (wolves, foxes), Ursidae (bears), Procyonidae (raccoons and relatives), Mustelidae (weasels, badgers, and relatives), Mephitidae (skunks), and Felidae (cats).

Five canids occur in the Chihuahuan Desert (ignoring the domestic dog). Wolves (Canis lupus) now are extirpated, but Coyotes (Canis latrans) is common throughout. The common fox of the mountains and other areas of rough topography is the Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). This is a good climber and occasionally may be found in trees as well as in precipitous rocky areas. Out in the desert basins, the Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis) is the common fox. Some workers consider the Kit Fox as a subspecies of the Swift Fox; the Swift Fox range centers in the Great Plains. Rare, and perhaps not really to be considered a member of the desert fauna, the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) is extremely marginal in the north.

The Black Bear (Ursus americanus) occurs primarily in mountain ranges in the Chihuahuan Desert region, but may wander into other habitats on occasion. The Grizzly Bear Ursus arctos) was common in parts of the region but is now extirpated.

Three members of the Procyonidae occur. The Ringtail (unfortunately often called Ringtail Cat) is Bassariscus astutus. Much more svelte and nimble than the Raccoon, it is at home in trees and rocky areas. Ringtails tend to be somewhat more carnivorous than its relative, the Raccoon. Raccoons are common now, at least in the northern desert region, along major drainageways and in montane forest. It seems to thrive best in the region where it can freeload to some degree on human garbage and crops. It's absent from the desert fossil record, athough occurring to the east and on the West Coast; it may have entered the desert region when humans opened up a "garbage" niche. The last member of the family is the Coati. This large member of the family usually travels in bands of up to well over a dozen individuals. The U.S. portion of the desert is marginal, with records from the bootheel area of New Mexico and adjacent Arizona and from the Big Bend. Many records may be of "solitarios"—males wandering alone beyond the main range of the species.

Two species belong to the Mustelidae: the Long-tailed Weasel (Mustela frenata) and the Badger (Taxidea taxus. As is the case in other weasels, the Long-tailed Weasel is long-bodied and short-legged. Weasels are built to go into burrows after prey, and as a group show adaptations in size for particular size classes of prey (or perhaps particular size classes of burrows). The Black-footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes) is a relatively large weasel adapted for prairie dog predation; it occurred in the region during the last ice age and possible later. The Long-tailed Weasel is of a size to go after most ground squirrels. Farther north, there is a weasel built for mouse-size prey.

The Badger isn't built to go into a burrow after its prey. Rather, it's built to dig them out. Powerful forelimbs and front claws are well adapted for this. It's habitat is extremely wide, from lower desert to timberline areas farther north.

Until fairly recently, most authorities accepted skunks as a subfamily of the Mustelidae; the general acceptance now is that they are different enough to be elevated to full family status as the Mephitidae. Four species occur through much of the area. Most common in most places is the Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis). The Western Spotted Skunk (Spilogale gracilis) is generally less common, but widespread. Another species of Mephitis, M. macroura (Hooded Skunk) is rare along the U.S./Mexico boundary, but widespread to the south. Finally, the Hog-nosed Skunk (Conepatus leuconotus) occurs throughout the region. In most of the literature until recently, the Western Hog-nosed Skunk (Conepatus mesoleucus) was considered to be the species of our region; however, it and the eastern species have been found to be conspecific (belonging to the same species), and the name C. leuconotus has priority under the rules of zoological nomenclatue.

All of the skunks have carried the development of anal glands (widely used in a number of mammals for scent marking) to an extreme. The odor is overpowering to many other mammals, and damage to the eyes, including blindness in extreme circumstances, may occur. The spray can be directed quite accurately. Most skunks will give warning signs before spraying unless startled. This often includes the stamping of the feet. The Spotted Skunk sometimes carries things further and will do a handstand (and is capable of spraying while doing so).

The Felidae is made of the cats. Two cats are common within the desert region (ignoring the domestic cat) and two marginal. The Bobcat (Lynx rufus) and Mountain Lion (Felis concolor) are found throughout. The Jaguar (Panthera onca) is marginal on the east and west, but seems to be increasing its presence in part of its original range along the Arizona/New Mexico border. The Ocelot (Felis pardalis) is more problematical, but may occasionally enter the desert region near Big Bend.

Almost every species of cat has been assigned to its own genus at one time or another. The classification used here is conservative, with three genera recognized for North America: Lynx for the short-tailed Bobcat (and the Canadian Lynx of the North); Panthera for the big cats (Jaguar, African Lion, Tiger, etc.); and Felis the small cats (some not so small: Mountain Lion). Puma is used by some as the genus for the Mountain Lion and Leopardus for the Ocelot.

Last Update: 27 Jun 2006