The map of the Chihuahuan Desert by Schmidt (1979) shown above is one of many interpretations possible. The Centennial Museum's Chihuahuan Desert pages show some of the variations.

The following description of the physical and climatic characteristics of the Chihuahuan Desert relies mostly on data from Schmidt (1986). The Chihuahuan Desert is a relatively high desert, with base level (basin floors) running mostly from 900 to 1200 m (ca. 3000 ft to 4000 ft), and it's big. It spans more than 11° from north to south and covers some 357,000 km2 (137,840 mi2). In general the lower elevations tend to be on the eastern side, with the desert floor sloping upwards to the central and western portions. As will be seen in the section on geology and topography, numerous mountain ranges bound the desert basins. These are mostly northwest trending mountains that generally rise some 600 to 1200 m (ca. 2000 to 4000 ft) above the basin floors. Schmidt considered 1800 m (ca. 6000 ft) as the upper limit of Chihuahuan Desert climatic conditions, and thus the higher of these ranges support non-desert climatic regimes. Such ranges, supporting non-desert plants and animals, often are known as sky islands, and they usually are considered as part of the Greater Chihuahuan Desert Region; we'll adopt that attitude here.

Schmidt's 1986 paper is available as a PDF file.

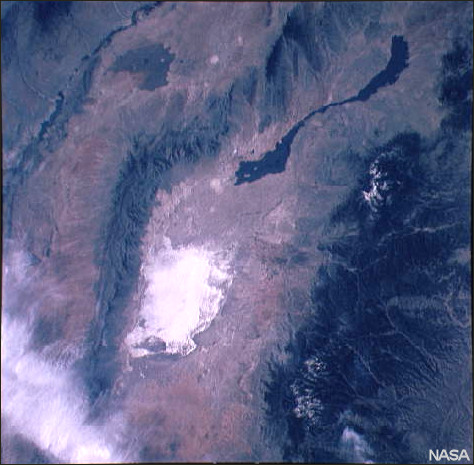

The Tularosa Basin and vicinity. In common with much of the Basin and Range physiographic province, mountains bound a closed basin (San Andres Mountains on the left, Sacramento Mountains on the right). White Sands National Monument and surrounding gypsum sands and the black Carrizozo lava beds to the north of the white sands are clearly visible. The Rio Grande passes diagonally across the upper left corner, integrating what otherwise would be closed basins. The wispy white area in the lower left corner consists of clouds. Photograph by NASA Johnson Space Center (photograph ID: STS003-10-614).

The Chihuahuan Desert is considered to be one of the most diverse desert regions of the world. However, much of the area has been degraded historically by human activity, likely along with some climatic change. Much of the region now covered with creosotebush and honey mesquite was in desert grassland in earlier historic time. Cathryn Hoyt's paper in the Endangered Species Bulletin gives some feel for this, as does Hall's (1990) analysis of pollen in the Hueco Bolsón, where grass pollen fell from 46% to 16% between the base and the top of a coppice dune.

Last Update: 19 Aug 2009