The ecology of many mammals is revealed, to a degree, by their teeth. Molars with grinding surfaces of blunt, little hills are the hallmark of such critters as bears, pigs, and ourselves, mammals that will eat almost anything. The slicing teeth of carnivores denote them as predators.

Among the herbivores, the crown height is a giveaway. The crown is the

part above the gum line, covered by resistant enamel. Brachyodont teeth are low

crowned, suitable for eating relatively soft foods; harsh food would wear away the

teeth before completion of the reproductive cycle. The molars of such mammals as

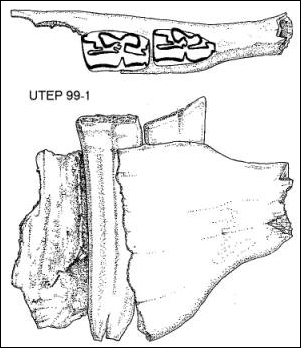

ourselves, packrats, and deer are representative. Hypsodont teeth are high crowned,

able to grind away at abrasive food, such as grasses, for extended periods before

wearing to the roots. Horses are a prime example, with crowns several inches long,

mostly buried in the jaws until slowly erupting as the grinding surface wears away.

Finally, the epitome of longevity, hypselodont teeth, evergrowing. Next time a rodent

smiles at you, note its front teeth—hypselodont incisors that will never wear

out.

Listen to the Audio (mp3 format) as recorded by KTEP, Public Radio for the Southwest.

Contributor: Arthur H. Harris, Laboratory for Environmental Biology, Centennial Museum, University of Texas at El Paso.

Desert Diary is a joint production of the Centennial Museum and KTEP National Public Radio at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Fragment of the lower jaw of a fossil horse showing the extremely hypsodont condition. The second tooth (p3) of this young individual is seen in its natural position. The crown extends down to just above the cleft separating the roots. Drawing of Laboratory for Environmental Biology specimen no. 99-1.