The Geomyoidea, consisting of the Geomyidae and Heteromyidae, is a New World taxon. Characters uniting the taxa include not only the presence of external, fur-lined cheek pouches, but also basic similarities in teeth and some skull structures.

Included in the Heteromyidae are pocket mice, kangaroo mice, spiny pocket mice, and kangaroo rats. Only the first and last groups are within our area (kangaroo mice [Microdipodops] are basically Great Basin animals, and spiny pocket mice [Liomys] are southern taxa reaching only as far north as the lowermost reaches of the Rio Grande Valley in Texas and almost north to the Arizona border in Sonora).

A taxonomic change in recent years has been the elevation of the subgenus Chaetodipus of the genus Perognathus to the generic level. From the practical point of identification, as it now stands, Perognathus includes what may be called the silky pocket mice, with relatively fine hairs making up the pelage, while Chaetodipus includes forms with harsh hair and weak spiny bristles on the rump.

| Perognathus flavescens | Chaetodipus baileyi | Dipodomys merriami |

| Perognathus flavus | Chaetodipus eremicus | Dipodomys ordii |

| Chaetodipus hispidus | Dipodomys spectabilis | |

| Chaetodipus intermedius | ||

| Chaetodipus nelsoni | ||

| Chaetodipus penicillatus |

Smithsonian Field Guide, Animal Diversity Web.

This group of rodents are well fitted for xeric conditions. All appear to have kidneys able to concentrate urine to the point where, if necessary, they can subsist on water gained solely from their food. Extended nasals allow condensation of moisture during exhalation, reducing respiratory loss (incidentally, camels have carried this to a fine art—during inhalation, special nasal tissues moisten the incoming air; during exhalation, these tissues absorb much of the moisture). Activity is limited mostly to nocturnal and crepuscular times, when the relative humidity tends to be greatest. During the day, they are in relatively cool, moist burrows, often with openings blocked. The pocket mice also appear to go into a torpid state easily (some of the smaller species having daily torpidity), slowing metabolism.

All of our heteromyids have grooved upper incisors, and the infraorbital foramen is on the size of the rostrum. These features can be seen in Fig. 1.

The pocket mice are primarily seed eaters and generally feed on a variety of kinds. They tend to rely more on individual finds of seeds lying on the surface or shallowly buried than the kangaroo rats, which tend to rely more on fewer kinds and on clusters of seeds assembled by the wind in depressions or shrubbery. The silky pocket mice tend to occur in grassy areas without shrubs as well as in shrubby habitats; Chaetodipus (other than the Hispid Pocket Mouse) tends to be limited to shrubby areas.

Fig. 1. Rostral area of a Dipodomys skull showing the grooved upper incisors and the infraorbital foramen on the side of the rostrum typical of heteromyids.

The two species

of Perognathus are similar in appearance for the most part. Perognathus flavescens may actually consist of two species (Frey

(2004): P. flavescens from the eastern grasslands and P. apache from west of the Pecos. Both occur in grassland, and P. apache may occasionally be found in lower woodland

habitats. The population of the latter from White Sands is notable for its very pale pelage that blends well with the white, gypsum sand. The Silky Pocket mouse (P. flavus) differs from the

other species by larger size, tending to be in the 5-6 g range) and to possess postauricular patches. P. flavescens is slightly larger and longer-tailed than P. flavus, with fewer

black hairs among the tan hairs of the dorsum and with smaller postauricular patches (nearly covered by the small ears).

The two species

of Perognathus are similar in appearance for the most part. Perognathus flavescens may actually consist of two species (Frey

(2004): P. flavescens from the eastern grasslands and P. apache from west of the Pecos. Both occur in grassland, and P. apache may occasionally be found in lower woodland

habitats. The population of the latter from White Sands is notable for its very pale pelage that blends well with the white, gypsum sand. The Silky Pocket mouse (P. flavus) differs from the

other species by larger size, tending to be in the 5-6 g range) and to possess postauricular patches. P. flavescens is slightly larger and longer-tailed than P. flavus, with fewer

black hairs among the tan hairs of the dorsum and with smaller postauricular patches (nearly covered by the small ears).

Fig. 2. Comparison of Perognathus and Chaetodipus skulls. Perognathus flavus skull on left, Chaetodipus eremicus skull on right. Zygomatic arches and lacrimals are damaged or missing. Note the relative sizes of the mastoid bullae and interparietals.

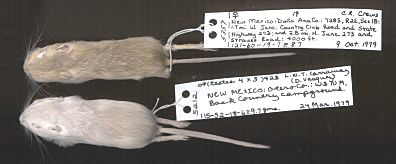

Fig. 3. Study skins of Perognathus flavescens. The upper specimen is from Doña Ana County, NM; the lower, from White Sands National Monument in Otero County, NM. The very pale coloration of the latter allows it to blend in with the white gypsum sands.

Where both species

occur, which is most of our region below pinyon-juniper woodland (and into woodland to some degree), flavescens/apache favors a sandy substrate and P. flavus a harder soil. Members of

the genus differ from Chaetodipus by the characters mentioned in the key.

Where both species

occur, which is most of our region below pinyon-juniper woodland (and into woodland to some degree), flavescens/apache favors a sandy substrate and P. flavus a harder soil. Members of

the genus differ from Chaetodipus by the characters mentioned in the key.

There are only two species of Chaetodipus common in our region, the Rock Pocket Mouse (C. intermedius) and the Chihuahuan Pocket Mouse (C. eremicus). The range of the Hispid Pocket Mouse (C. hispidus) includes most of the state except the northwestern quarter, but appears relatively sparse except in the Great Plains area. The range of Bailey's Pocket Mouse (C. baileyi) is limited to the Peloncillo Mountains area along the Arizona border, and Nelson's Pocket Mouse (C. nelsoni) occurs in the Trans-Pecos portion of Texas but in New Mexico has been taken (only once) solely in the Carlsbad area (4 mi W of White City). The Desert Pocket Mouse (Perognathus penicillatus) barely enters New Mexico along the Arizona border. Most of the literature until recently treats the Chihuahuan and Desert pocket mice as a single species (Perognathus or Chaetodipus penicillatus); the split is based primarily on molecular data, the two species qualifying as cryptic species.

Chaetodipus intermedius and C. nelsoni are both rock-dwelling pocket mice and are very similar in characteristics (see key). Both have rump spines, but these may not be evident at some times. The restriction to rocky situations will usually separate these two species from C. penicillatus and C. eremicus (very strongly limited to non-rocky areas) and from C. hispidus, which usually is in medium to tall grass or tall annual forbs in areas of friable soil. The size of C. baileyi, larger than the others, usually will be enough to identify it; additionally, it, C. penicillatus, and C. eremicus lack rump spines.

The kangaroo rats (Dipodomys) have carried some of

the characteristics seen in pocket mice (enlarged mastoid bullae and a tendency toward saltatorial locomotion) to extremes. The mastoid bullae form much of the skull (Fig. 3), apparently being

specialized for picking up the faint sounds made by the usually silent flight of owls as the owl brakes to seize its prey during an attack. Being vulnerable by doing much of their foraging in open

spaces, there is strong natural selection for hearing such sounds in time to execute a "panic jump" that may carry it out of reach of the owl. The hind limbs are adapted for jumping, whereas the

forelimbs are relatively small and weak. Locomotion often is via the hind limbs alone.

The kangaroo rats (Dipodomys) have carried some of

the characteristics seen in pocket mice (enlarged mastoid bullae and a tendency toward saltatorial locomotion) to extremes. The mastoid bullae form much of the skull (Fig. 3), apparently being

specialized for picking up the faint sounds made by the usually silent flight of owls as the owl brakes to seize its prey during an attack. Being vulnerable by doing much of their foraging in open

spaces, there is strong natural selection for hearing such sounds in time to execute a "panic jump" that may carry it out of reach of the owl. The hind limbs are adapted for jumping, whereas the

forelimbs are relatively small and weak. Locomotion often is via the hind limbs alone.

Fig. 4. Dorsal view of the skull of a Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys spectabilis). LEB Resource Collections specimen.

Three species occur in the region. Merriam's Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys merriami) is a southern form reaching north a bit beyond central New Mexico. Although sometimes sympatric with Ord's Kangaroo Rat (D. ordii), it tends to prefer a harder substratum rather than the sandier habitat preferred by Ord's. The handiest feature for discrimination between the two is the presence of only four toes on the hind limbs of D. merriami versus five for D. ordii. Ord's Kangaroo Rat extends from within Mexico in Canada. The Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat is larger than either of these species and it's tail is tipped with white (and thus the common name). Its range extends to the Four-Corners area of northwestern New Mexico. The geographic ranges of all three species extend far south into Mexico.

Last Update: 12 Feb 2008

Centennial Museum and Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Texas at El Paso