We have the natural tendency to think of other animals and of plants as being basically similar to ourselves. And often they are. Some, though, are very different indeed. We believe having separate male and female individuals is natural, and tend to sneer at such animals as snails that are hermaphrodites—both male and female. Perhaps if snails weren't quite so slow-witted, they would consider us as the odd ones.

Many plants, likewise, figuratively march to the beat of a different

drummer. Some, like our desert's Four-wing Saltbush, divide up the sexes

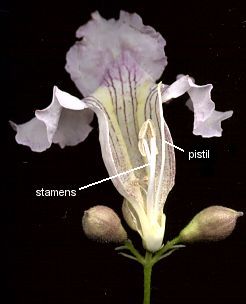

"properly", but many kinds have both female and male parts. In a so-called

perfect flower, the centrally placed pistil contains the ovules, or eggs. The

surrounding stamens are the male structures that produce pollen—pollen that results in

fertilization of the eggs. But even here, variety rules. Some kinds of plants fertilize

themselves; others never do. And more than a few refuse to rely on risky sex alone,

producing new plants from other parts of their bodies—parts as sexless as any

stone.

![]()

Contributor: Arthur H. Harris, Laboratory for Environmental Biology, Centennial Museum, University of Texas at El Paso.

Desert Diary is a joint production of the Centennial Museum and KTEP National Public Radio at the University of Texas at El Paso.

A "perfect" flower (the example shown is a Desert Willow). Left: The lower portion of the fused petals has been removed to reveal the sexual parts. Right: A close-up, showing the flower in more detail.

The Ecotree. A game to learn the parts of a flower.