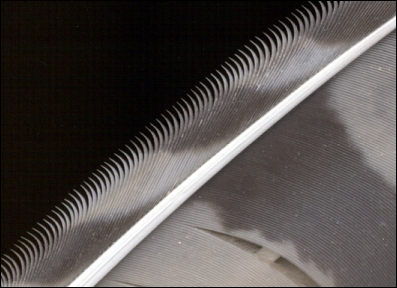

Most bird owners have no trouble telling when their pet is flapping its wings—the noise of wings beating the air is unmistakable. Certainly humans aren't the only animals who can hear this noise, so some hunting birds, like the Great Horned Owl, have strategies to silence it. Though most birds have a straight edge along the front of their wings, owls have a soft fringe on the leading edge, muting the sound as they drift silently through the night skies.

Large eyes help them see at night, and their ears are even positioned

at different heights on the sides of their heads. This helps the owls calculate the

position of anything that makes a noise. If it sounds promising, they shift to attack

mode, plummeting silently toward their unsuspecting victim. Little does the prey know

that it is about to take another step up the food chain.

Listen to the Audio (mp3 format) as recorded by KTEP, Public Radio for the Southwest.

Contributor: Kodi Jeffery, Centennial Museum, University of Texas at El Paso.

Desert Diary is a joint production of the Centennial Museum and KTEP Public Radio at the University of Texas at El Paso.

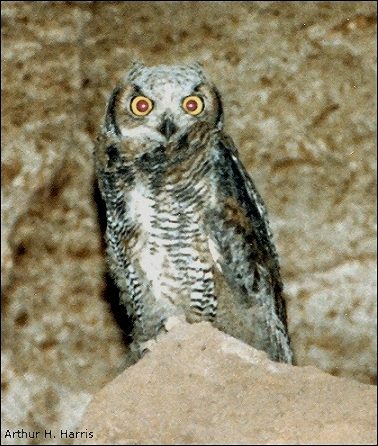

A Great Horned Owl in U-Bar Cave, 16 June 1985. The pupils of the eyes ordinarily are black, but in this image are reflecting the camera's flash. Photograph by A. H. Harris.

The silencing fringe on the leading edge of the owl wing can be seen clearly, running diagonally from lower left to upper right, in this scanned image. View is from the underside of the wing.

Austing, G. R., and J. B. Hold. 1966. The world of the great horned owl. Lippincott, Philadelphia.

Bent, A. C. 1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. Part 2. Smithsonian Institution, U.S. National Museum Bulletin 70.

Craighead, J. J., and F. C. Craighead. 1956. Hawks, owls and wildlife. The Stackpole Co., Harrisburg.

Errington, P. L., F. Hamerstrom, and F. N. Hamerstrom. 1940. The great horned owl and its prey in north-central United States. Iowa State College. Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 277:757 850.

Heinrich, B. 1987. One man's owl. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Johnsgard, P. 1988. North American owls. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

McInvaille, W. B., and L. B. Keith. 1974. Predator prey relations and breeding biology of the Great Horned Owl and Red-tailed Hawk in central Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 88(1):1-20.

Sparks, J., and T. Soper. 1970. Owls, their natural and unnatural history. Taplinger Publishing Company, New York.

Tyler, H. A., and D. Phillips. 1978. Owls by day and night. Naturegraph Publishers, Happy Camp, CA.

Voous, K. H. 1988. Owls of the Northern Hemisphere. Collins, London.

Welty, J. C. 1982. The Life of Birds, 3rd ed. Saunders College Publishing, Philadelphia, 754 pp.

The Owl Pages. Images and basic life history information concerning the Great Horned Owl.