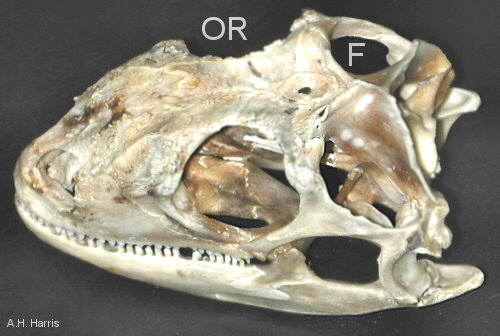

Most people wouldn't consider having holes in their skulls as a good thing beyond, of course, our normal complement. Goes to show that looking around at our desert inhabitants and even into our own fossil background can be instructive. Taking our own history back in time first, there comes a place when great grandfather, many time removed, was a reptile, and lo and behold, an extra hole in the side of his head about where our temple is. Apparently this allowed the lower jaw muscles, which attached inside the outer layer of bone, to bulge while chewing.

But enough about us what about other animals? We're fresh out of

alligators locally, but they have two pairs of extra holes. Lizards used to, but being

progressives, got rid of one of them. Now you may not think of snakes, who had lizards

as ancestors, as being radicals, but there you go—it's shed both pairs. If you

don't like this kinship with serpents, how about birds? They too have shucked off

two pairs of holes, and now, like us, are hopefully the better for it!

Contributor: Arthur H. Harris, Laboratory for Environmental Biology, Centennial Museum, University of Texas at El Paso.

Desert Diary is a joint production of the Centennial Museum and KTEP National Public Radio at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Skull of an iguana. "OR" indicates the position of the orbit (eye socket) and "F" that of the temporal fenestra (the extra "hole" in the head) on the far side of the skull. The openings can be seen clearly on the near side of the skull, directly below the labels. Laboratory for Environmental Biology specimen; photograph by A.H. Harris.